In this issue:

- Will an ATC corporation actually benefit airlines?

- The Hill publishes debunked ATC reform claims

- NextGen vision not being implemented—Inspector General

- Controller strikes: Europe vs. the United States

- Further perspective on electronic flight strips

- Upcoming Event

- News Notes

- Quotable Quotes

Will ATC Corporatization Actually Yield Benefits?

Just days after the wrap-up of A4A’s fourth annual Commercial Aviation Industry Summit, a bizarre headline on an opinion piece in The Hill asked whether ATC “privatization” is “a solution in search of a problem.” That piece coincided with some aviation blog discussions along the lines of the old saw that airline delays are the fault of limited airport runway capacity, not a technically backward ATC system.

And indeed, airline speakers at the A4A event did cite the padding of airline block times that disguises the increases in flight times in recent decades, while pointing to an inadequate ATC system as a cause. For example, JetBlue CEO Robin Hayes noted that the block time built into airline schedules today for New York-Washington flights is 80 minutes, compared to 60 minutes several decades ago. To be sure, since no new runways have been added at JFK, LGA, EWR, or DCA during this time period, while flight activity has increased, today’s longer scheduled flight times do reflect runway limitations.

But runway “capacity” is not an absolute. For example, better technology and procedures introduced by NATS for time-based separation (TBS) of flights on approach to Heathrow have increased the landing rate during strong headwinds from 32-38 per hour with conventional fixed spacing to 36-40 per hour using TBS. Even more dramatic is the potential recently demonstrated at SFO via a combination of RNP approaches and a GBAS (GPS-based) landing system. Based on recent tests, reported Guy Norris in Aviation Week (Sept. 12-25, 2016), “the system would enable aircraft to land at normal rates, even in low visibility” (when landing rates are typically cut in half). Yet for a variety of funding and cultural reasons, FAA has not made GBAS part of NextGen, and has made very slow progress implementing “real” RNP approaches that save time and fuel.

Corporatized NATS and Nav Canada in 2015 began implementing reduced lateral separation on their North Atlantic tracks, with the distance between parallel tracks reduced from one degree of latitude (60 nm) to one-half degree (30 nm). Phase 1 did this only for an initial pair of tracks, adding a third one between them. Phase 2, beginning early next year, will extend this to all North Atlantic tracks. The benefits to customers equipped with ADS-B and Controller-Pilot Data Link will be far more frequent access to the flight tracks with the best tailwinds (eastbound) or the least headwinds (westbound), saving time, fuel, and CO2 emissions. Once Aireon’s space-based ADS-B surveillance is available, in-trail separations will also be reduced, for further customer gains.

The connection between corporatization and these kinds of customer benefits should be obvious. A customer-focused organizational culture, better in-house technical skills, businesslike procurement, and reliable funding from ATC fees have been making these kinds of gains happen a lot faster at corporatized air navigation service providers (ANSPs) than is possible at FAA.

Thus, it is quite logical that airline CEOs speaking at the A4A event vowed continued efforts to transform the FAA’s Air Traffic Organization into a user-funded, stakehold-governed ANSP next year, when Congress returns to the FAA reauthorization issue. That’s also why controllers’ union president Paul Rinaldi and his NATCA colleagues continue to push for this kind of reform. As Rinaldi told summit attendees, “When I get to travel around the world and see what [equipment and technology] our counterparts are using—especially in Canada and the UK—you have to shake your head. We don’t have the best equipment in the U.S.”

And as reporter Michael Bruno noted in Aviation Daily, when Congress develops next year’s FAA reauthorization bill, their September 30th, 2017 deadline is precisely when “sequestration budget cuts are scheduled to come back into full force.” So don’t look for any meaningful FAA funding increases in that reauthorization.

The Hill Publishes Debunked ATC Reform Claims

In an effort to be fair to both sides in the debate over ATC corporatization, The Hill on September 30th published an op-ed that repeated many previously-debunked claims against the idea put forth over the past year by opponent Delta Airlines.

Author R.W. Mann repeats opponents’ misleading characterization of the plan as “privatization” in which Congress would “turn over control of the US ATC system to a private board dominated by representatives recommended by commercial airlines.” It’s not “privatization” in any of the usual senses of the word; it’s a transformation of the existing ATO. Governance would be entrusted to a 13-member stakeholder board, of which only four members would be recommended by airlines (who would be paying well over 90% of all fees and charges). That’s hardly “domination.”

The piece goes on to argue the position discussed in this newsletter’s lead article that corporatization would not produce any benefits for airlines, since the real problems are either limited runway capacity or airlines’ own lack of focus on on-time service. Mann points out that only Delta has invested in software to better manage flight punctuality, in effect giving away the store on Delta’s effort to forestall reforms that would undercut its current competitive advantage.

But the piece’s worst claims come straight out of Delta’s discredited playbook:

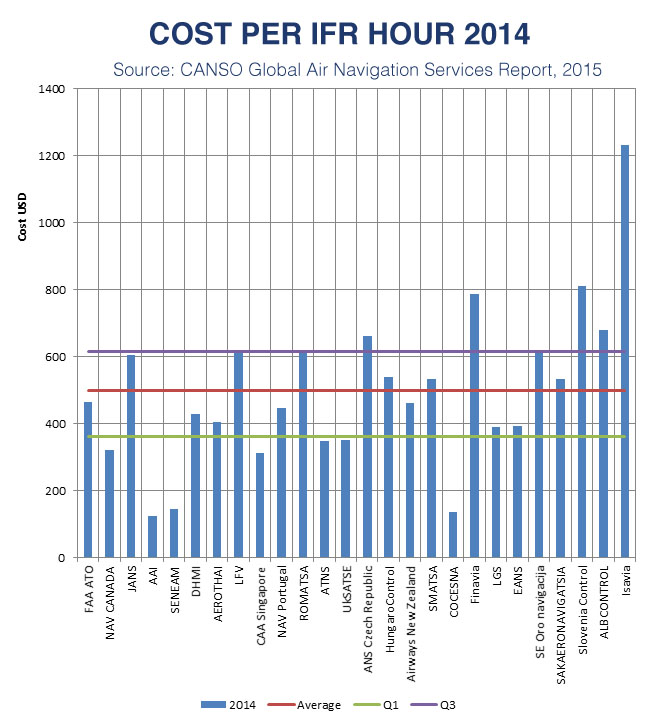

- That Nav Canada’s ATC services are more costly than those of the FAA, ignoring internationally recognized datasets—converted to US dollars—that show the opposite (see graph below).

- That NATS was so badly run that it “required a bailout by UK taxpayers”—a distortion of the fact that 9/11 devastated UK air traffic only a few months after the corporatization of NATS and that each of its several owners (including the government) made additional equity investments to get it through the near-term aftermath.

- That a UK commission found that there were “unambiguous signs of strain” on UK air service. That report was by the UK Airports Commission, and it was discussing the shortage of runway capacity in southeastern England. It had nothing whatsoever to do with ATC provider NATS.

These claims have all been debunked in print before, in this newsletter and elsewhere. To repeat them at this juncture suggests that Delta and its friends have no real arguments against corporatization to put forward.

NextGen Vision Not Being Implemented—Inspector General

In December 2004, DOT Secretary Norm Mineta and FAA Administrator Marion Blakey released the very ambitious Next Generation Air Transportation System Integrated Plan. Representing the views of seven federal agencies (including DOD and NASA), the report laid out a vision for transforming U.S. air transportation by 2025. There would be significantly expanded airport and ATC system capacity, increased safety, better security, and many other good things. The plan aimed to “virtually eliminate [airport] surface delays,” give cockpit crews situational awareness of nearby aircraft, permit (in designated airspace) cooperative self-separation, provide for 4-dimensional flight path prediction, and achieve performance equivalent to that in visual meteorological conditions during instrument meteorological conditions. To coordinate the long-term R&D among the various agencies involved, Congress approved creation of the Joint Planning & Development Office (JPDO).

Well, that was then and this is now. The end-date of 2025 is just nine years away. How’s that vision doing? The DOT Office of Inspector General (OIG) released a kind of status report on August 25th, “FAA Lacks a Clear Process for Identifying and Coordinating NextGen Long-Term Research and Development” (AV-2016-094). Its purpose was to assess what has happened since Congress, frustrated over FAA’s failure to establish a clear role for the JPDO, terminated its funding in 2014. In response, FAA established its own Interagency Planning Office (IPO) to coordinate NextGen R&D between FAA and other federal agencies. The OIG report acknowledges that FAA has made some progress, for example with IPO having defined six high-priority R&D areas, for three of which NASA has the lead responsibility.

But the report goes on to discuss serious problems, such as:

- The six high-priority areas have not been validated by FAA’s own Research, Engineering, and Development Committee (REDAC) or other outside experts.

- FAA has not updated the nine-year old NextGen R&D plan developed by JPDO in 2007.

- The IPO is not addressing other potential high-priority R&D areas previously identified by the JPDO that, if not pursued, “could materially affect the pace of NextGen in the longer term.”

But the most important paragraph in the entire report, which received zero media attention, is the following:

“A longer-term vision is particularly important because the original vision for NextGen is not what is being implemented today. As the National Research Council (NRC) noted last year, NextGen has been redefined, and not all parts of FAA’s original vision will be implemented in the foreseeable future. In addition, our work—and a 2014 MITRE assessment of NextGen progress—has shown that NextGen’s success depends on FAA shifting from deploying infrastructure to transitioning new and enhanced operational capabilities into operational use.”

The question OIG does not address is why things have turned out this way. There are several reasons, not just one. First, some of what was laid out in the 2004 Integrated Plan was very likely unrealistic. Second, FAA’s chronic funding woes led to understandable pressure from its aviation customers—acting through the NextGen Advisory Committee—to engage in a kind of triage, focusing what resources it has on near-term goals that would produce tangible gains. But the third reason stems from FAA’s conservative bureaucratic culture.

I wrote a long report on this problem in 2014, commissioned by the Hudson Institute (https://reason.org/files/air_traffic_control_organization_innovation.pdf). And since then I continue to receive emails from former FAA ATC experts, now in private industry, providing further documentation. Here is an example from a 36-year FAA veteran now in the private sector. “In 2014 I was involved in a major airspace redesign between Cleveland Center (ZOB) and Nav Canada. The two contractors working at ZOB would tell me regularly how decisive Nav Canada was and always on schedule. [Eventually] Nav Canada informed our people that if ZOB wasn’t on schedule, they were making the changes anyway, which would have resulted in their new Q routes ending at the US/Canada border. Under that pressure, FAA somehow stayed on schedule.”

Another example comes from the remote-tower pilot project in Leesburg, VA. “The FAA hierarchy changed the certification requirements three times in 15 months. As someone with over 50 years of ATC experience, I would not hesitate to certify this system with some minor tweaks. Unfortunately, there are no ATC types at FAA who have ever worked in a tower without radar, and therefore many thought this system was not adequate because they couldn’t see a Cessna 172 three miles from the airport. I can certify that you can’t see a C172 looking out tower cab windows either, at that distance, and it is not required.” He concluded his memo to me, “I think that in almost all cases the overriding deterrent to innovation and modernization is that no one in the FAA bureaucracy wants to accept the risk for implementing new technology and procedures. The FAA’s Safety Management System has surely had the unintended consequence of making a sluggish bureaucracy into one that can’t act on even the most benign changes.”

One of the main conclusions of my Hudson Institute study was that ATC reform requires more than just revamping the system’s funding and governance. It also requires institutional reform that can create a less risk-averse and more innovative organizational culture. We see that culture at work in corporatized providers like Airways New Zealand, DFS, NATS, and Nav Canada. Depoliticization and separation of ATC provision from safety regulation are among the keys to bringing about this kind of culture change.

Controller Strikes: Europe vs. the United States

U.S. airlines and their passengers have been well-served by the long-standing federal ban on strikes by air traffic controllers. Current law requires FAA controllers to take an oath that they will not break the law by going on strike, and we all know that President Reagan fired the striking PATCO controllers who refused his ultimatum to return to work on penalty of being fired.

Contrast the relative labor peace in U.S. air traffic control with the situation in Europe. Recent years have seen one strike after another, at both corporatized ANSPs and traditional government transport agencies. France has had something like 40 ATC strikes over the past decade alone. The only airline that has called for outlawing controller strikes is Ryanair, whose CEO Michael Leary last year launched an online petition drive for which he hopes to obtain one million signatures, calling on the European Commission to somehow override the labor laws of several dozen European Union members. Almost as fanciful are recent calls from Airlines for Europe (A4E) to permit the ANSPs of other countries to provide replacement service in the airspace of a country whose controllers are on strike. So far A4E has not proposed how such a plan would be implemented (though if a Single European Sky was ever achieved, the consolidated facilities and consistent ATC procedures might make that technically possible).

The ATC corporation provisions of the bill approved by the House Transportation & Infrastructure Committee back in February are supposed to make controller strikes an illegal activity at the corporation, but the bill has been criticized by several conservative groups as not really doing that. The bill extends several provisions of 5 USC Chapter 71 to the ATC corporation; those are civil service provisions, but the corporation is clearly not intended to be covered by civil service regulations, so that is probably not the best way to implement the no-strike objective.

It would be wiser to include in the statute creating the corporation’s federal charter explicit language that controllers are prohibited from striking. I asked NATCA President Paul Rinaldi about this, and he said that he and NATCA have no interest in gaining a right to strike and would be fine with such a provision. When I explained that to a conservative labor expert recently, the reply was to ask for specifics on how that would be enforced. So some further discussion on the details may be warranted. Another expert I talked with recently, who favors corporatization, pointed out that requiring the employees of a private, nonprofit corporation to take an oath would be contrary to private-sector practice. Perhaps a simple provision could be included in the corporate charter mandating that all controller contracts include no-strike language under which going on strike is grounds for employee dismissal.

Further Perspective on Electronic Flight Strips

As many readers know by now, on July 6th FAA announced the winner of its competition to produce the Terminal Flight Data Manager (TFDM) system, which will finally replace paper flight strips with transferable electronic information on controllers’ screens. Lockheed Martin was the winner, beating out Northrop/Nav Canada and Harris/Frequentis. The sad news is that full implementation of TFDM is expected to take 12 years.

Two readers of this newsletter contacted me last month to gently chide me for implying that FAA was virtually the last developed country to shift from paper to electronic flight strips. Paul Mayo of Frequentis noted that most ANSPs in Europe still use paper, as do nearly all in Asia and all of those in Africa. As of now, he wrote, only the Frequentis and Nav Canada systems are in regular use: the former’s system in France, Hong Kong, Israel, and New Zealand and the latter in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Dubai, and Sweden. Several other vendors have installed systems that controllers do not use, because they are too distracting.

Another reader reminded me that FAA actually does have electronic flight strips in its three oceanic centers—ZNY, ZOA, and ZAN. The system, called Ocean 21, was adapted from a system developed for Airways New Zealand by CAE (which is no longer in the ATC business). The project to adapt and enhance it for Ocean 21 was called ATOP, adding radar interface and ADS-B support as well as a conflict probe. My informant (who asked not to be named) told me that the system has been in operation for 10 years now.

So in this limited portion of its ATC system, FAA was something of a pioneer in electronic flight strips, along with Airways New Zealand and Nav Canada. But with a growing number of ANSPs now equipped, and more in the near-term pipeline, it’s still outrageous that the agency that thinks of itself as the world’s best will not have systemwide electronic flight strips until more than a decade from now.

Note: I do not have the space to list all aviation events that might be of interest to readers of this newsletter. Listed here are only those at which a Reason Foundation transportation researcher is speaking or moderating.

Transportation Research Forum, DC Chapter, Oct. 19, 2016, Old Ebbitt Grill, Washington, DC (Robert Poole speaking). Details at: http://www.trforum.org/chapters/washington.

LFV and Saab Launch Remote Tower Company. Sweden’s corporatized air navigation service provider LFV and remote tower pioneer Saab have launched a joint venture company, called Saab Digital Air Traffic Solutions. The company, 59% owned by Saab, will design, build, sell, and certify remote towers anywhere in the world. Saab developed for LFV the world’s first operational remote tower center, which has been in operation since April 2015 controlling traffic at the distant Ornskoldsvik Airport. Saab is also operating a demonstration project at the airport in Leesburg, VA.

GlobalBeacon Announced by Aireon and FlightAware. A private-sector response to ICAO’s call for a Global Aeronautical Distress and Safety System (GADSS) was announced last month by space-based ADS-B company Aireon and flight tracking company FlightAware. Their GlobalBeacon service will offer continuous tracking worldwide, using Aireon’s soon-to-be-launched global ADS-B satellite constellation and FlightAware’s existing flight-tracking network. GADSS calls for routine tracking at least every 15 minutes in non-radar airspace, switching to one-minute updates only when in distress mode. But GlobalBeacon will offer continuous tracking all the time at one-minute updates.

DFS Wins Edinburgh Tower Contract. Germany’s corporatized air navigation service provider DFS last month was announced as the winning bidder to provide control tower services at Edinburgh, Scotland—the sixth-largest UK airport. It was the second UK win for the control tower division of DFS, following its 2014 selection to provide tower services to Gatwick International Airport. The corporatized UK air navigation service provider, NATS, formerly held the Edinburgh tower contract.

Multilateration Certified for Bratislava Airport, Slovakia. The Slovak Republic’s air navigation service provider, LPS, has received certification for a new multilateration (MLAT) airfield surveillance system for Stefanik Airport in Bratislava. Delivered and installed by Comsoft Solutions, the system is interfaced with LPS’s nationwide ADS-B surveillance system. MLAT is updated more frequently than conventional secondary surveillance radar, resulting in more accurate real-time surveillance.

ADS-B Coming to New Zealand Airspace in 2019. All aircraft in controlled airspace above 24,500 feet in New Zealand Airspace must be equipped with ADS-B/Out by the end of December 2018. To prepare for this, the country’s corporatized ANSP, Airways New Zealand, has awarded a contract to Thales to install a network of ADS-B ground stations, beginning early in 2017. New Zealand’s mountainous terrain has limited radar surveillance, but the ADS-B system will fill in those gaps. Current plans call for expanding the requirement for ADS-B equipage to all lower altitudes by 2021, when the current radar system is to be decommissioned.

Introduction to Remote Towers, Scientific American. Readers of Scientific American‘s blog can get up to speed on the remote tower concept, thanks to a guest blog by aviation researcher Ashley Nunes. “Air Traffic Control without Towers” provides a good introduction to the subject for non-aviation readers. (https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/air-traffic-control-without-towers)

Seychelles Signs Up for Space-Based ADS-B Surveillance. Aireon LLC has signed up a second ANSP customer in Africa. The Seychelles Civil Aviation Authority (SCAA) early this month announced a service contract (data service agreement) with Aireon covering the entire Seychelles Flight Information Region. Its 2.63 million square miles includes extensive oceanic airspace and borders the FIRs of India, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Somalia, and Tanzania. Aireon’s first African customer is ATNS, the corporatized ANSP of South Africa.

House Passes Bill for GPS Backup System. On September 26th, the U.S. House passed unanimously a bill by Reps. John Garamendi (D, CA) and Duncan Hunter (R, CA). It requires the Coast Guard to develop an electronic successor to the legacy Loran system, called eLoran, as a backup to GPS for all civil and military uses. It would broadcast enhanced long-range signals from 19 towers around the country, providing overlapping fields to permit triangulation.

ATC Commercialization Study to Change Websites. The first comprehensive empirical study of before-and-after performance metrics of corporatized ANSPs, Air Traffic Control Commercialization: Has It Been Effective?, will no longer be available on the MBS Ottawa website after October 26th. MBS Ottawa carried out the study in conjunction with George Mason University, McGill University, and Syracuse University. (www.mbsottawa.com). After October 26th, it will still be available via the Social Science Research Network (http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1317450).

Corrections to Last Month’s Newsletter. The report on issues involved in ATC reform/transition by the Government Accountability Office, discussed in last month’s issue, was not a draft but was actually the finished product. The online version of last issue’s newsletter has been corrected to reflect that, and the report is available on the GAO website as GAO-16-386R. Also, an alert reader noticed that the name of the Jeppesen company had been misspelled. Our apologies for both errors.

NextGen Updates from FAA. The library section of the FAA website (http://www.faa.gov/nextgen/library) includes four relatively new documents: Future of the NAS (summing up NextGen as envisioned to 2025), NextGen Implementation Plan 2016, NextGen Business Case 2016, and Chief NextGen Officer Report to Congress.

“It’s past time to remove politics from air traffic control and put it under an independent, nonprofit organization funded entirely through user fees and with representation from all stakeholders, including airlines. This model has proven successful in more than 60 countries. It would allow the Federal Aviation Administration to focus on doing the job it does best: regulating safety.”

—Robin Hayes, CEO, JetBlue Airlines, “Antiquated Air Traffic Control Hurts New York Economy,” Crain’s New York Business, August 18, 2016

“NextGen needs a new path forward. Though America’s ATC system is second to none, its technology is still stuck in the 1950s. NetGen is starting to change that, albeit in fits and starts. Some argue that changing the current funding and governance structure would hinder its progress—that’s just nonsense! It is today’s system that has hampered a more-timely and effective implementation of NextGen. It is telling that the National Air Traffic Controllers Association, which has a substantial stake in this debate, agrees the current status does not work. ATC reform would accelerate the progress in implementing NextGen with a more reliable source of funding while creating incentives to deliver projects on time and on budget.”

—Former Sen. Byron Dorgan, “5 Things You Need to Know about Air Traffic Control Reform,” The Hill, Dec. 16, 2015

“Milestones marking technological implementation are key to [ATC] modernization, but turning on new technology is not the goal of NextGen and SESAR. Improving the safety and efficiency of air traffic management is the goal. . . . So our celebrations need to be focused on seeing operational improvements in the air traffic system—are we flying from one city to another faster than we were before, or using less fuel than we were before. Those are the milestones we should be marking.”

—Neil Planzer, Boeing, “System of Systems,” Air Traffic Management, Quarter 2, 2016

“Having to do a slow-start on your capital projects every year due to Continuing Resolutions, facing occasional government shutdown, and having your overall capital budget constrained by spending caps makes it hard to implement multi-year, transformative capital programs like the FAA’s NextGen air traffic control modernization. This is one reason why various legislators and blue-ribbon panels since 1987 have recommended various plans to separate the [ATO] from the rest of government and insulate them from the vicissitudes of the federal budget process.”

—Jeff Davis, “Government Stays Open Under CR, But on a Limited Basis,” Eno Transportation Weekly, October 3, 2016

—Andy Shand, “Time-Based Separation: Time to Take Control,” Airspace, Quarter 3 2016