Even with a recent slowdown in housing sales as interest rates remain high, the long-run crisis in housing affordability in many parts of the nation remains. A close look at recent trends in zoning policy can inform policy decisions for alleviating high housing prices. Regulations and restrictions on the housing market contribute significantly to the cost of housing development and account for much of the affordability problem. Research suggests that accumulated regulatory barriers add 20-50% to the cost of housing—often deemed the “regulatory tax”—via restrictions on the supply of affordable development. Zoning policy is one major contributor. Zoning laws intend to restrain negative externalities arising from development incompatible with a neighborhood’s character and goals.

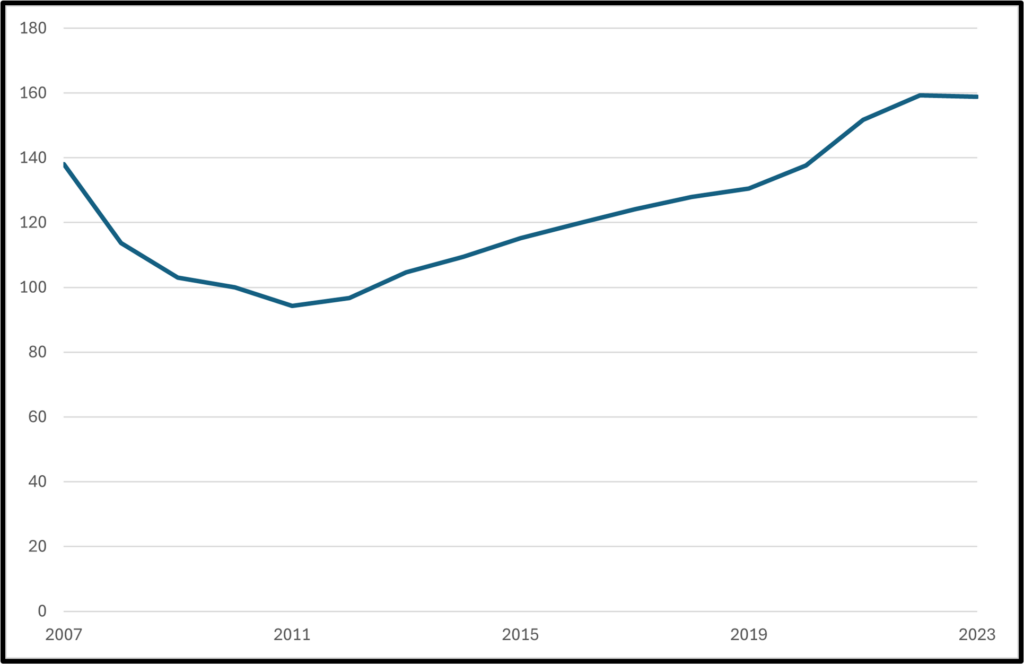

The zoning law of an area influences its every aspect, including development type, traffic, and property values. These laws are typically decided on the municipal level, as cities consider the best ways to organize their specific communities. Despite admirable goals, excessively restrictive zoning policies are common and put housing out of reach for many. As local leaders look for cost-effective means for dealing with the rising housing costs (see Figure 1), trends suggest an increasing openness to zoning reform.

Figure 1: U.S. Real Residential Property Prices where 2010=100

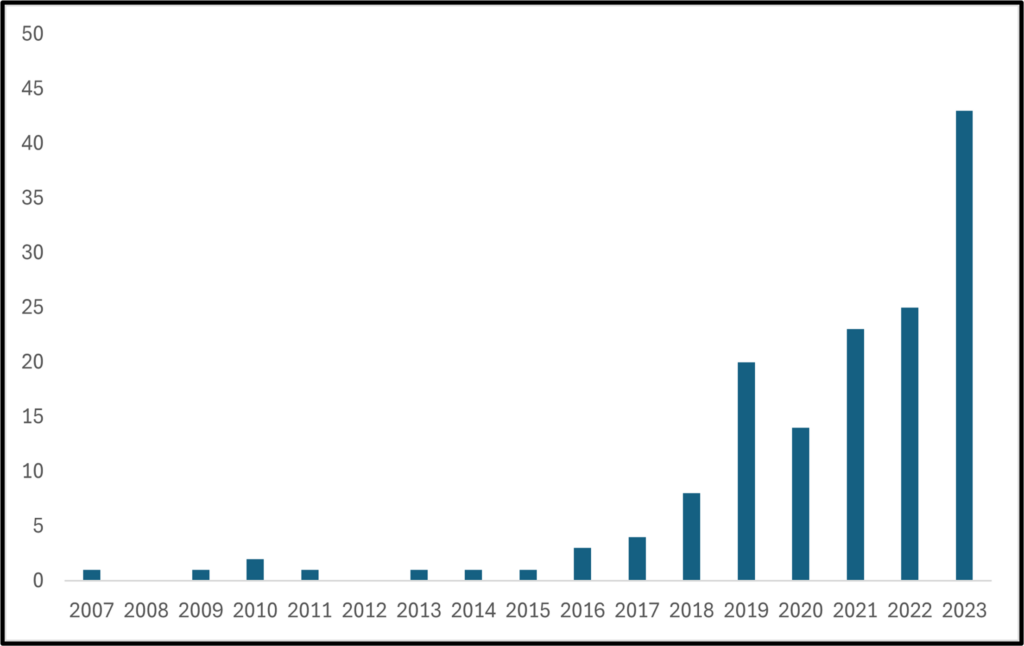

The University of California, Berkeley’s Othering and Belonging Institute (O&B) has compiled a database of the major municipal zoning reform efforts across the United States between 2007 and 2023. The Othering & Belonging Institute researchers have also written a series of articles explaining the database. The data and insights reveal a budding acceptance of zoning reform that favors property-owner choice and density. Visualizing the data through charts and reviewing critical case studies can help display the trend toward reform and what barriers still stand in the way of change.

Figure 2: Number of Zoning Reform Attempts 2007-2023

The housing crisis and zoning reform

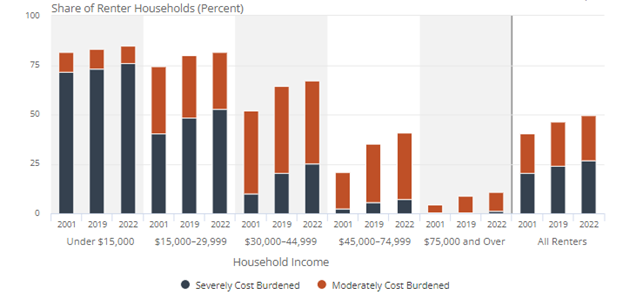

The recent skyrocketing of zoning reform attempts coincides closely with the rise in home prices nationwide. Recent findings suggest that as of 2022, nearly 42 million American households (including renters and owners) are “cost-burdened,” spending more than 30% of their income on housing. This is an increase of nearly 5 million since 2019. A tightening of housing supply in the aftermath of the Great Recession, significant regulation around development, and population shifts have led to the steady climb of real home prices. For renters, as Figure 3 shows, the number of cost-burdened households is growing and affecting households at all income levels, but it is most severe in the lowest tiers. As municipal leadership grows increasingly concerned with the lack of affordable and available housing, some have turned to zoning reform as a solution.

Figure 3: Cost Burdens Climb the Income Scale

Years of compounding regulatory barriers have led the housing market to its current state. Zoning codes and standards are enacted to address specific concerns about the character of a city (ex., minimum lot sizes, height restrictions, development type restrictions, etc.) Codes tend to remain once enacted. Dr. Jessica Trounstine, professor of political science at Vanderbilt University, has described how this accumulation of regulatory barriers over time contributes to a rise in home prices. Strict, “exclusionary” zoning codes and population growth (especially around metropolitan areas) each place upward pressure on prices. The primary goal of recent zoning reform is to facilitate property owners’ ability to create new housing and eliminate arbitrary barriers to additions to the housing supply. This can be achieved through several policy avenues.

Types of zoning reform

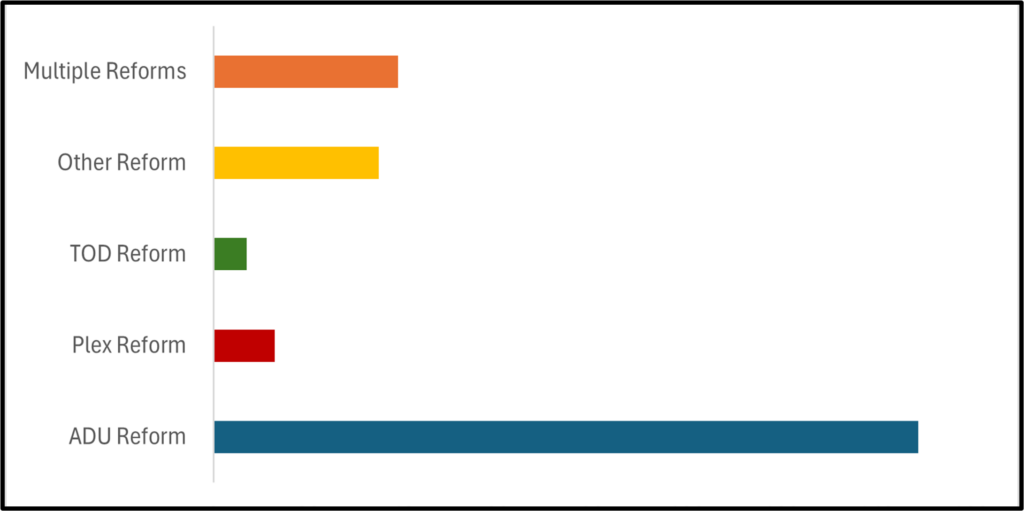

Zoning reform most often takes the form of “upzoning“—increasing the density permitted in a certain area. Upzoning can take many subtle forms, including raising height restrictions, lowering minimum parking lot size requirements, and raising permitted floor-to-area ratios. In its standard form, however, it is altering the compositions of suburbs to permit developments that are not exclusively single-family detached homes. Some of the most popular types include accessory dwelling units, plex, and transit-oriented deveopment reforms.

Accessory dwelling units (ADUs)

The most common type of zoning reform is overwhelmingly the loosening of regulations around accessory dwelling units (ADUs). ADUs are smaller residential buildings constructed on the same plot of land as a larger single-family home, typically housing one or two people. Their popularity is mainly due to being “infill.” This means they do not require denser housing development but rather provide property owners with the opportunity to build another unit on their land. Instead of radical change to the zoning landscape and massive, intrusive construction projects, Accessory dwelling unit reform allows additional housing to be added to existing and fully developed neighborhoods. ADUs are also a popular option for non-rental housing for extended family members. So much so that they are often colloquially referred to as “granny flats” or “in-law units.”

Accessory dwelling unit reform is an affordable housing policy tool that promotes mutual gain and voluntary additions to the housing supply. When policy allows ADUs to be rented out, their smaller size and building costs mean lower rents for tenants when compared to traditional single-family homes. This feature makes them especially suitable for lower-income individuals, should they be rented out. The income generated from collected rents is also a clear benefit to the primary homeowner—now functioning as a landlord with one property.

This low-hanging fruit of zoning reform is among the most popular. Municipal changes around ADUs include allowing them to be used as long-term rental properties, expanding the quantity permitted on one parcel, or allowing them to be built by default without needing permission from a regulatory body. Flexibility around ADU development is a case where the supply of affordable housing can be expanded simply by allowing entrepreneurial homeowners to use their property in the way that is most beneficial to them. More significant reforms have proven more challenging to pass.

Plex reforms

As of 2019, 75% of all residential land in the United States was zoned exclusively for single-family detached homes. This restriction dramatically hinders the construction of higher-density, and consequently higher-affordability, units on most residential-zoned land. Besides contributing to the rise of home prices for middle- and low-income individuals, exclusive single-family home zoning has been associated with community disconnect, car dependency, and a stifling of neighborhood diversity.

Zoning codes are not simply part of the legal code of an area but an integral part of the culture and a reflection of public sentiment. The Not-In-My-Backyard (NIMBY) movement is a coalition of often single-family homeowners that oppose changes to their community’s character through new projects. Higher crime, degradation of neighborhood character, lower property values, and a strain on public resources are often-cited concerns of NIMBY proponents. However, the severity of the current housing crisis has created a political climate more conducive to moderate density amendments in the form of “plex reforms.”

Plex reforms are rezoning ordinances that allow the development of “plex” developments (duplex, triplex etc.) in certain single-family zoned neighborhoods. These housing types have also been called “missing middle housing,” referring to their lack of availability compared to single-family homes and high-density apartments. In contrast to the homeowner-targeted ADU allowances, these regulatory amendments are for commercial developers seeking to add to the broader housing stock. It should be noted that these reforms often do not apply to properties restricted by deed covenants and conditions, such as in HOAs.

These amendments, like ADU reforms, are a form of “light-touch density.” This term has been used to describe incremental increases in an area’s density. Plex reforms expand flexibility in zoning codes, making light-touch density possible in ways more palatable to community members than large apartment buildings.

Transit-oriented development (TOD)

While ADU and plex reforms are powerful tools to address housing abundance, they do not directly address community interconnectedness. Transit-oriented development centers not only increase housing supply but the creation of desirable communities.

Transit-oriented development (TOD) is a planning approach that maximizes walkability and access to public transportation, often by increasing the permitted density and mixed-use development within a certain radius of a public transportation center. After housing, transportation is the largest expenditure for the average American household. TOD reform focuses first and foremost on walkability and accessibility of public transportation; hence, it is transit-oriented. It is an unorthodox approach to zoning policy—rather than strictly segregating different zones for singular uses; TOD encourages compatible but diverse development. The TOD approach prioritizes flexible zoning for housing types and interlaced commercial and residential zones. Dense, mixed-use zoning is a top priority. With further freedom for developers and increased leniency in density under TOD, lower housing costs are expected as a natural byproduct.

Despite their promises of community flourishing and interconnectedness, TOD reforms have proven rare, likely due to their scope. The Othering & Belonging Institute Zoning Reform’s Sortable Database reports only eight such reform attempts—one of which was rejected.

Figure 4: Types of Zoning Reform 2007-2023

How successful are zoning reform attempts?

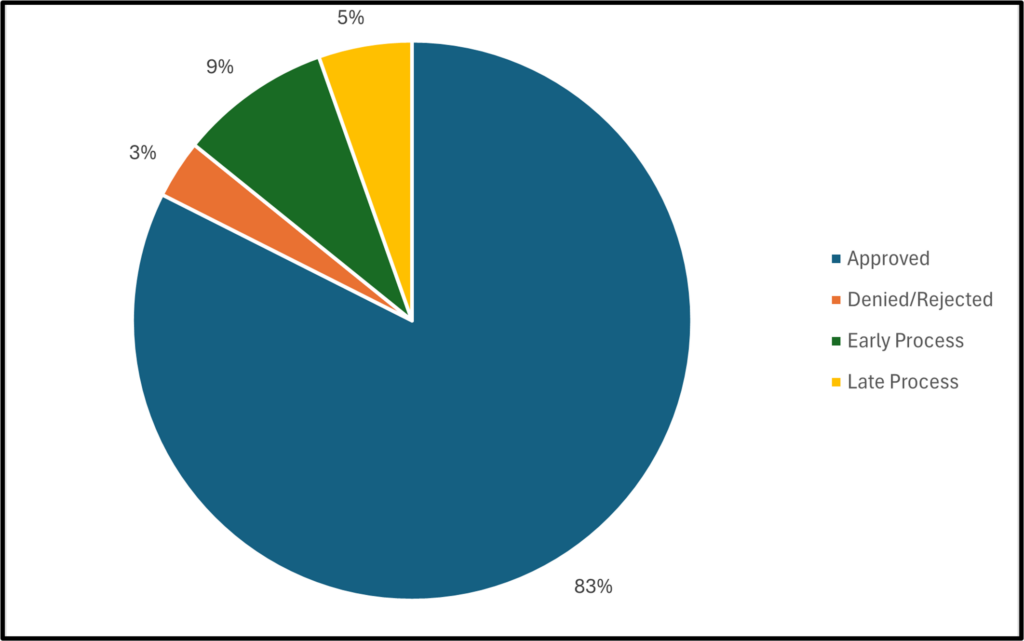

Examination of the O&B Zoning Reform database reveals a high approval rate for all zoning reform types. An overwhelming 83% of proposed reforms completed their course through the legislative process and cemented themselves as a part of local law. In these cases, the community saw the benefits of upzoning and ultimately decided it was the right choice. Equally interesting to those seeking reform, however, are the cases where calls for reform were unsuccessful. What were the influences at play? What critical mistakes can be avoided?

Figure 5: Phase of Zoning Reforms

These cases are rare. In fact, of 148 municipal zoning reform attempts recorded, only five were outright denied, and some are still in the approval process. However, each denied case offers unique insight into community sentiments on zoning reform and the potential roadblocks that can arise when reforming legislation.

Anchorage, Alaska: Other reform (zoning simplification)

In early 2023, members of the Anchorage Assembly proposed a collapse of the current 15 different residential zoning codes into only two in a reform titled AO 2023-66. The two districts would be titled R and R-OUS, each including residential development of various densities, including mixed-use development. The only difference between the proposals is that R-OUS developments may have limited access to “infrastructure and municipal service.” Simplifying the Anchorage zoning code was proposed to eliminate barriers to housing construction, specifically for reducing homelessness through the private market. This proposal, called the “Housing Opportunities in the Municipality for Everyone” (HOME), was not rejected outright, but public outrage over the seeming destruction of single-family home zoning led to amending the initial plan. In some cases, sweeping reform may prove too unpalatable for a community to accept outright. Updates to the amended version are pending as of the time of this article.

Gainesville, Florida: Plex amendment

In central Florida, local commissioners have reversed affordable housing strides. On April 19, 2023, the Gainesville County Commission voted 4-3 to reverse the elimination of single-family zoning, adopted in October 2022. Residents of single-family home neighborhoods raised persistent opposition to reform. Following the passing of the initial ordinance, single-family homeowners complained of receiving calls that offered to buy their homes to develop apartments and plex units. Vocal members of the public grew increasingly worried about the potential change to their communities’ character if someone agreed to take the deal and voiced their concerns to the commissioner’s office. Reform pitted the right of property owners to build more density on their land, or sell their property for redevelopment into more units, against neighbors’ desire to have only single-family homes nearby.

Like the zoning simplification attempt in Anchorage, public outcry from single-family homeowners proved the tipping point in the decision to reenact exclusionary zoning policy. These groups typically have the resources and organizational abilities to advocate for their interests in the local political sphere. In cases where zoning reform appears to threaten the goals of the existing community, it is likely to face organized, and often successful, resistance. One way to alleviate this might be to limit the redevelopment density in single-family neighborhoods to 2 or 3 units. Another might be to simplify the creation of homeowners’ associations where property owners can voluntarily preserve the neighborhood character rather than using zoning to impose it on everyone.

Atlanta, Georgia: Transit-oriented development and ADUs

In a bid to increase community interconnectivity and housing affordability in Atlanta, City Councilman Amir Farokhi introduced three ordinances (21-0-0454 through 21-0-0456). These ordinances each targeted a narrow aspect of zoning reform (TOD, land-use reform in the comprehensive plan, and ADUs, respectively). The two mentioned in the O&B zoning tracker under the category “rejected/denied” include the first and the third.

In detail, the first was a TOD reform that aimed to rezone all low-density residential land within a half-mile radius of a “high capacity” transit station to allow medium-density development. These medium-density units are called “multifamily residential multi-units,” or MR-MU.

The third was a proposal to allow the construction of accessory dwelling units (within specified limitations), as well as eliminate parking space requirements for single-family homes.

On December 6, 2021, the ordinances were filed and referred to the zoning review board and zoning committee. Once there, the ordinances were voted on by Atlanta’s Neighborhood Planning Units (NPUs). NPUs are advisory committees composed of an area’s citizenry that make recommendations on land use and zoning-related matters. There are 25 in Atlanta. Ultimately, they voted 18-6 (one abstained) to reject the combined ordinances, which had been renamed for their purposes as “Z-21-74 – Housing Diversity.”

Investigation of the NPUs’ meeting minutes in which the ordinances were rejected reveals some key insights. The minutes of NPU-E’s meeting on October 5, 2021, reveal that committee members did not believe developers wanted to build affordable housing. One committee member said that “an increase in density does not necessarily result in affordable housing.” Further, there were concerns that eliminating parking requirements would increase traffic without having the desired effect of lowering the price of housing. The members of NPU-E ultimately rejected the ordinance 21-1.

Atlanta’s case is like the others mentioned in that community members expressed their disapproval and ultimately stopped the ordinance. However, the similarities essentially end there. From the little information available from NPU-E, the concern seems to be with the inefficacy of the reform rather than the efficacy. Those who objected were concerned that the ordinance would not add to the supply of affordable housing, making it not worth the risk of the change in community character that accompanies potential new additions (as was the case in Anchorage and Gainesville). There is a distinct distrust that developers are interested in building dense, affordable housing.

Further, the idea of eliminating parking requirements was troubling to some. The impression appears to be that once parking requirements are removed, developers will build without lots and driveways, leaving residents to park on the street and creating substantial traffic problems. This understanding begs the question: If some construction feature is not legally required, will developers always choose to forgo it? Perhaps not. The removal of the requirement does not necessitate developers will never incorporate adequate parking into their projects. Instead, developers will now have the option to cater their buildings toward residents who do not own cars, and as a result of fewer costs, potentially offer more affordable units. If they project their residents will want to park, they have every incentive to create structures that are livable for their client base.

Carmel, Indiana: Accessory dwelling units

In 2021, a broad ADU ordinance was attempted in Carmel, Indiana. This reform would not only have made it possible to build an ADU without explicit approval from the Board of Zoning Appeals (BZA) but also required 20% of all new residential developments with 10 or more lots of one acre or less to include them. After a lengthy series of revisions, this legislation was rejected 8-0. Primary concerns centered on the requirements for ADU inclusion, which was rightfully seen as an incursion on consumer choice. In the editing process, the ADU requirement provision was ultimately removed.

Instead, it was replaced with a recommendation from the land-use committee that all new ADUs must receive approval from the Board of Zoning Appeals (BZA)—essentially nullifying its original intent of eliminating barriers to ADU additions. Diluting the ordinance, coupled with pushback from members of HOAs who worried about eyesore ADUs if regulations were loosened, created the perfect storm for a unanimous rejection. When passing reform, simplicity and clarity should be prioritized. Rather than adding to the bloated book of rules for property owners, homeowners, and developers, successful zoning reform tends to strip away barriers. Carmel, Indiana, is one of the cases where the tendency to over-complicate proposed legislation proved detrimental.

Zoning reform challenges and who’s leading the way

As local governments seek to combat rising home prices, some kinds of zoning reform have proven more politically feasible than others. Zoning reform through political channels can be difficult due to the imbalance in representation between those who would benefit from a repeal of exclusionary zoning and those who believe they benefit from the status quo.

Commission boards and other elected officials legislate according to the represented interests of their communities. To vote in an NPU meeting, ID must be presented to prove residency to the NPU’s jurisdiction. Provisions like this make sense in principle but have created serious limitations for policy reform and representation. In such cases, the existing residents of a community (often single-family homeowners) can clearly state their concerns and present a firm, organized opposition to zoning reform. Meanwhile, the potential beneficiaries of proposed affordable developments are left with no voice. In such a system, the most obvious method for change is convincing existing members that there are benefits to economic and development diversity; and that property rights matter while neighborhood character is best achieved through HOAs and similar organizations. Otherwise, one would have to eliminate the political element from the zoning process, which is not obviously possible or necessarily desirable. Persuasion and gradual steps seem to have yielded the most success so far, though each community and situation is vastly different.

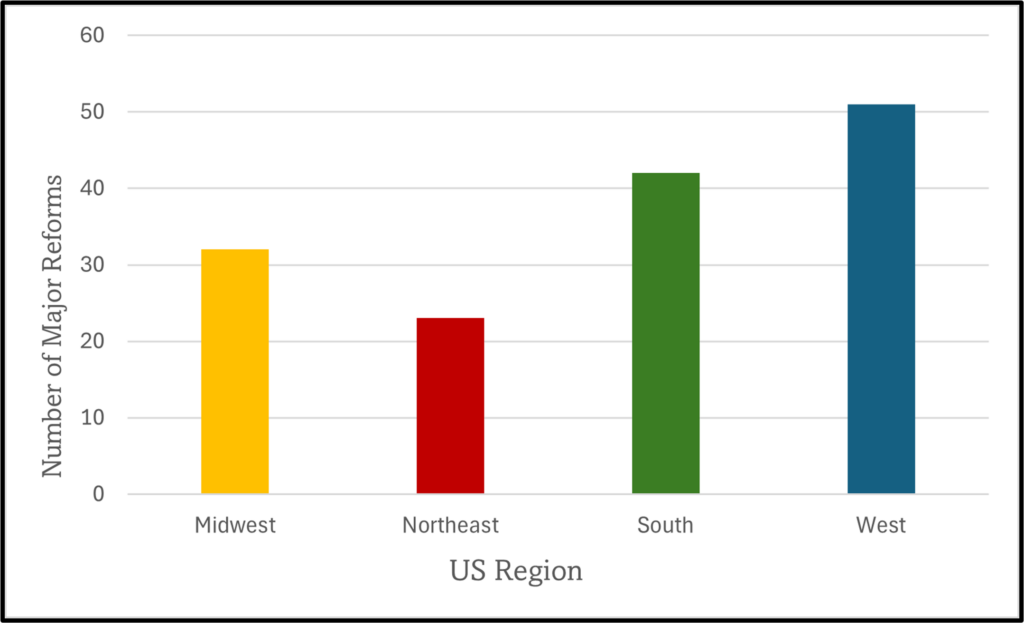

Figure 6: Zoning Reform by Region

Table 1: Delineation of states & number of reforms in each

| Northeast | South | Midwest | West | |

| Connecticut (2) | Arkansas (1) | Illinois (3) | Alaska (3) | |

| Maine (3) | D.C. (1) | Indiana (2) | Arizona (4) | |

| Massachusetts (5) | Florida (4) | Iowa (2) | California (14) | |

| New Jersey (3) | Georgia (6) | Michigan (6) | Colorado (2) | |

| New York (4) | Kentucky (4) | Minnesota (9) | Idaho (1) | |

| Pennsylvania (4) | Louisiana (1) | Missouri (1) | Montana (1) | |

| Vermont (2) | Maryland (1) | Ohio (3) | Nevada (1) | |

| North Carolina (9) | South Dakota (1) | New Mexico (1) | ||

| Tennessee (3) | Wisconsin (4) | Oregon (4) | ||

| Texas (6) | Utah (4) | |||

| Virginia (6) | Washington (15) | |||

| Wyoming (1) | ||||

| Notes: States with no zoning reforms were not included in the original database and are omitted from this table. Further, this database contains only municipal reforms and does not include statewide initiatives. | ||||

Despite varying quantities of reform, most regions make their zoning code nearly identically: Municipalities zone their land, with any land left over (“unincorporated land”) zoned by the county. However, different legislative histories and tendencies may inform outcomes.

The 2019 National Longitudinal Land Use Survey by the Urban Institute illuminates some of the regulatory barriers on residential land in the Northeast that make it so resistant to reform. As of 2019, compared to the other regions of the United States, the Northeast stands out for:

- Lowest amount of residential land zoned for maximum density development (30+ units per acre)

- Among the highest minimum sizes (in square feet) for both single-family and multifamily dwellings

- Among the highest requirements for the number of off-street parking spaces for multifamily units

- A close second to the Midwest in ADU regulation and restrictions.

Historically, the Northeast has had among the most restrictive land-use policies in the country. Understanding this regulatory tendency can inform the hesitance to embrace flexible zoning reform practices. Local governments in the Northeast have been generally favorable toward regulations on development, and if they were to seek reform, they would have the most policies to reverse.

The West, on the other hand, leads the zoning reform, closely followed by the South. California and Washington have been home to some of the most sweeping zoning reform policies at the state and municipal levels. In the 2019 National Longitudinal Land Use Survey, the West and South had opposite results compared to the Northeast: lower development requirements (parking minimums, minimum sizes etc.) and more allowance for higher-density development. In fact, in 2019, over 80% of residential land in the West allowed ADU construction by right or with a ministerial use permit. That amount has only increased since then. The Western states have taken impressive strides toward housing affordability, becoming the model for zoning reform and flexibility.

Housing development is time-consuming, and so is waiting for the market to adjust to a higher housing supply after a prolonged affordability crisis. Tangible results from these reforms are not yet solidified, but there are indicators that these are steps in the right direction. A statewide case study regarding ADU reform from California suggests a willingness of property owners and developers to respond to changes in zoning structure.

In 2016, the California state government passed laws that required municipalities to allow ADU construction on most residential land. Between the preemption and the end of 2022, an estimated 80,000 ADUs have been constructed across the state, with 27% qualifying as low-moderate income housing. In California, when property owners were given the choice to develop their land in a way beneficial to them and their communities, many took the opportunity. It may not be overly optimistic to assume that given the same freedoms, other property owners, developers, and landlords will do the same.

Conclusion

Municipalities are turning to zoning reform to remedy the nationwide affordable housing shortage. Since 2016, the number of reforms proposed per year has skyrocketed. Loosening regulation around accessory dwelling units is overwhelmingly the most popular option, but plex reforms and transit-oriented development are also valuable avenues. While lighter, less-unintrusive ordinances (like accessory dwelling unit reforms) are seeing great general success in making it into law, NIMBY sentiment has proven a setback in some cases. Analysis of five rejection cases finds that community action groups and single-family homeowners are particularly resistant to zoning reform. Additionally, doubt that zoning reform is effective lingers among some community members. And even so, reforms are rarely rejected.

Further, the regulatory history of an area can inform sentiments toward reform. Areas that have accumulated substantive zoning regulations, like the Northeast, are associated with fewer municipal zoning reform attempts in the future (and vice versa). These trends are reflected in the data collected by the Othering & Belonging Institute. The natural question for many is how effective these policies will ultimately prove in alleviating the ongoing housing affordability crisis. While it is still too early to say for many of the specific cases mentioned here, early evidence from other reforms in places like California, Michigan, and Minnesota, suggests there are reasons to be optimistic.