“It is not a government’s obligation to provide services, but to see that they are provided.”

—former New York Governor Mario Cuomo“Privatize everything you can.”

—Chicago Mayor Richard Daley (advice to an incoming mayor)

Over the last half century, governments of all political complexions have increasingly embraced privatization—shifting some or all aspects of government service delivery to private sector provision—as a strategy to lower the costs of government and achieve higher performance and better outcomes for tax dollars spent.

Recent decades have seen privatization shift from a concept viewed as radical and ideologically based to a well-established, proven policy management tool.1—Indeed, local policymakers in many jurisdictions in the U.S. and around the world have used privatization to better the lives of citizens by offering them higher quality services at lower costs, delivering greater choice and more efficient, effective government.

In the 21st century, government’s role is evolving from service provider to that of a provider or broker of services, as the public sector is increasingly relying far more on networks of public, private and non-profit organizations to deliver services.2—Virtually every local government service—from road maintenance, fleet operations and public works to edu cation, corrections and public health services—has been successfully privatized at some point in time somewhere in the world.

This trend is not confined to any particular region, or to governments dominated by either major political party. The reason for the widespread appeal of privatization is simple: it works. Decades of successful privatization policies have proven that private sector innovation and initiative can do certain things better than the public sector. Privatization also boosts the local economy and tax base, as private companies under government contract pay taxes into government coffers and offer employment to communities.

Privatization—sometimes referred to as contracting out, outsourcing, competitive sourcing or public-private partnerships—is really an umbrella term referring to a range of policy choices involving some shift in responsibility from the government to the private sector, or some form of partnership to accomplish certain goals or provide certain services. It covers everything from simple contracting to asset sales and joint ventures (see textbox below on common forms of privatization). Though often involving governments partnering with for-profit firms to deliver services, privatization can also involve partnering with non-profit organizations or volunteers.

All forms of privatization are simply policy tools—they can be effective when used well and ineffective when used incorrectly. The reason privatization works is simple: it introduces competition into an otherwise monopolistic system of public service delivery. Governments operate free from competitive forces and without a bottom line. Thus, program structures and approaches often stagnate, and success is not always visible and is hard to replicate. Worse, since budgets are not linked to performance in a positive way, too often poor performers in government get rewarded as budget increases follow failure.

Competition done right drives down costs and incentivizes performance. Private firms operating under government contracts have strong incentives to deliver on performance—after all, their bottom line would be negatively impacted by the cancellation of an existing contract or losing out to a competitor when that contract is subsequently re-bid. On the government’s side, applying competition forces management to identify the true cost of doing business, and, with efficiency as a goal, compels an agency to use performance measurement to track and assess quality and value. At its root competition promotes innovation, efficiency and greater effectiveness in serving the shifting demands of customers. Oftentimes, this allows contractors to provide comparable or even superior wages and benefits while reducing service costs and improving service levels.

Common Goals of Privatization

Government managers use privatization to achieve a number of different goals:

- Cost Savings: Competition encourages would-be service providers to keep costs to a minimum, lest they lose the contract to a more efficient competitor. Cost savings may be realized through economies of scale, reduced labor costs, better technologies, innovations or simply a different way of completing the job. A review of over 100 studies of privatization showed that cost savings ranged between 5 and 50 percent depending upon the scope and type of service; as a conservative rule of thumb, cost savings through privatization typically range between 5 and 20 percent, on average.3

- Improved Risk Management: Through contracting and competition, governments may be better able to control costs by building cost containment provisions into contracts. In addition, contracting may be used to shift major liabilities from the government (i.e., taxpayers) to the contractor, such as budget/revenue shortfalls, construction cost overruns, and compliance with federal and state environmental regulations.

- Quality Improvements: Similarly, a competitive process encourages bidders to offer the best possible service quality to win out over their rivals.

- Timeliness: Contracting may be used to speed the delivery of services by seeking additional workers or providing performance bonuses unavailable to in-house staff.

- Accommodating Fluctuating Peak Demand: Changes in season and economic conditions may cause staffing needs to fluctuate significantly. Contracting allows governments to obtain additional help when it is most needed so that services are uninterrupted for residents without permanently increasing the labor force.

- Access to Outside Expertise: Contracting allows governments to obtain staff expertise that they do not have in-house on an as-needed basis.

- Innovation: The need for lower-cost, higher-quality services under competition encourages providers to create new, cutting-edge solutions to help win and retain government contracts.

Forms of Privatization

While there are many different forms of privatization, some of the most common are:

- Contracts: The most common form of privatization in local governments occurs when governments contract with private sector service providers, for-profit or nonprofit, to deliver individual public services, such as road maintenance, custodial services, fleet maintenance and water system operations and maintenance. Local governments also routinely contract with private firms to provide administrative support functions, such as information technology, accounting and human resources. Local governments are also increasingly using “bundled” service contracts that integrate more functions or responsibilities into a single contract, such as a contract to outsource an entire city public works department.

- Franchises: In a franchise arrangement—also referred to as a lease or concession—government typically awards a private firm an exclusive right to provide a public service or operate a public asset, usually in return for an annual lease payment (or a one-time, upfront payment) and subject to meeting performance expectations outlined by the public sector. As an example, in many jurisdictions common utility services—such as telecommunications, gas, electricity and water—are provided through long-term franchise agreements. Franchise-based privatization initiatives may involve the privatization of an existing government asset, such as a toll road, water/wastewater plant or airport, though similar arrangements can be used to finance, build and deliver new infrastructure assets as well. Chicago’s $1.8 billion lease of its Chicago Skyway toll road, $1.15 billion lease of its downtown parking meter system, and $560 million lease of four downtown parking garages are recent examples of the franchise approach.

- Divestiture: Some forms of privatization involve governments getting out of a service, activity or asset entirely, often through outright sales. Local governments routinely sell off aging or underutilized land, buildings, and equipment, returning them to private commerce where they may be more productively used. For example, in the late 1990s New York City sold off two city-owned radio stations and a television station, and Orange County, California raised more than $300 million through real asset sales and asset sale-leaseback arrangements over the course of 18 months to help recover from collapse into bankruptcy in 1995.

Where Can—or Can’t—Local Governments Apply Privatization?

Local policymakers often ask a very simple question: “where can we apply privatization?” However, the answer is somewhat more complicated.

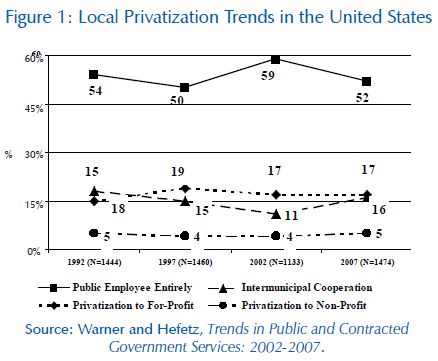

One obvious place to start is examining what other local governments are doing. The International City-County Management Association (ICMA) conducts a survey of alternate service delivery by local governments every five years, measuring service delivery for 67 local services across more than 1,000 municipalities nationwide. The 2007 survey shows that public delivery is the most common form of service delivery at 52 percent of all service delivery across all local governments on average (see Figure 1).4—For-profit privatization at 17 percent and intergovernmental contracting at 16 percent are the most common alternatives to public delivery. Non-profit privatization is next at 5 percent, and franchises, subsidies and volunteers collectively account for less than 2 percent of service delivery, on average.

Trends in levels of for-profit privatization and non-profit contracting have remained relatively steady over the last two decades (though the 2007 survey would not capture the likely uptick in local government privatization in the wake of the 2008-2009 recession and subsequent proliferation of state and local fiscal crises).

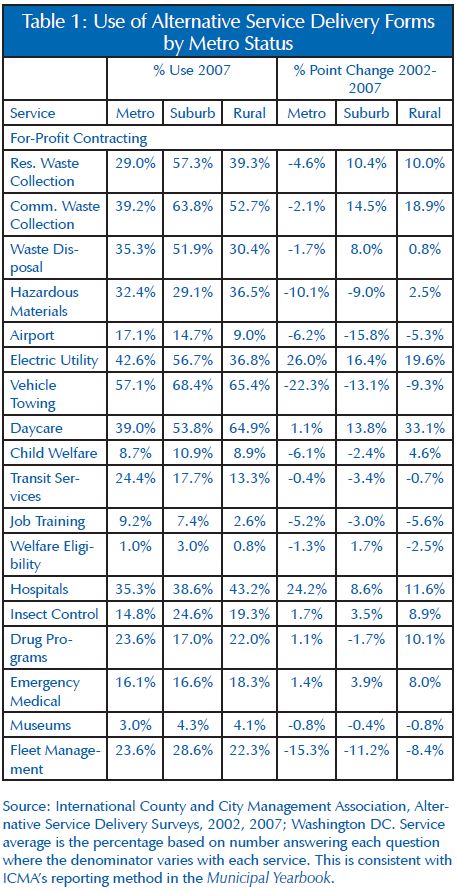

Table 1 shows the percentages of surveyed local governments using privatization across a range of public services. Among the most frequently privatized local government services are waste collection (residential and commercial), waste disposal, vehicle fleet management, hospitals, vehicle towing, electric utilities, drug programs and emergency medical services.

- Accounting, financial and legal services;

- Administrative human resource functions (e.g., payroll services, recruitment/hiring, training, benefits administration, records management, etc.);

- Core IT infrastructure and network, Web and data processing;

- Risk management (claims processing, loss prevention, etc.);

- Planning, building and permitting services;

- Printing and graphic design services;

- Road maintenance;

- Building/facilities financing, operations and maintenance;

- Park operations and maintenance;

- Zoo operations and maintenance;

- Stadium and convention center management;

- Library services;

- Mental health services and facilities;

- Animal shelter operations and management;

- School construction (including financing), maintenance and non-instructional services;

- Revenue-generating assets (garages, parking meters, etc.), and

- Major public infrastructure assets (roads, water/wastewater systems, airports, etc.).

This is but a partial list. But more important, the question of “what can local governments privatize” is in many ways the wrong question to ask, as privatization is a policy tool that should be considered in most instances.

A better question is “where can’t local governments apply competition or privatization?.” Virtually every service, function and activity has successfully been subjected to competition by a government somewhere around the world at some time. When asked what he wouldn’t privatize, former Florida Governor Jeb Bush replied: “—police functions, in general, would be the first thing to be careful about outsourcing or privatizing. This office. Offices of elected officials … and major decision-making jobs that set policy would never be privatized.” Governor Bush used competitive sourcing more than 130 times, saving more than $500 million in cash-flow dollars and avoiding over $1 billion in estimated future costs.

Privatizing City Hall: Sandy Springs and the New Georgia Contract Cities

What may surprise many local policymakers is the extent to which other communities have embraced privatization, extending the boundaries far beyond what’s seen in most jurisdictions. For example, over the last four years, five new cities serving over 200,000 residents have incorporated in metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia as “contract cities.” These newly incorporated cities opted to contract out virtually all of their non-safety related government services to private firms, dramatically reducing costs and improving services along the way.

Sandy Springs, Georgia was the first. Fed up with high taxes, poor service delivery and a perceived lack of local land use control, 94 percent of Sandy Springs’ nearly 90,000 people voted to incorporate as an independent city in 2005. What makes Sandy Springs interesting is that instead of creating a new municipal bureaucracy, the city opted to contract out for nearly all government services (except for police and fire services, which are required to be provided directly by the public sector under Georgia’s state constitution).

Originally created with just four government employees, the city’s successful launch was facilitated by a $32 million contract with CH2M-Hill OMI, an international firm that oversees and manages day-to-day municipal operations. The contract value was just above half what the city traditionally was charged through taxes by Fulton County. The city maintains ownership of assets and maintains budget control by setting priorities and service levels. Meanwhile the contractor is responsible for staffing and all operations and services. According to Sandy Springs Mayor Eva Galambos, the city’s relationship with the contractor “has been exemplary. We are thrilled with the way the contractors are performing. The speed with which public works problems are addressed is remarkable. All the public works, all the community development, all the administrative stuff, the finance department, everything is done by CH2M-Hill,” Galambos said. “The only services the city pays to its own employees are for public safety and the court to handle ordinance violations.”

Sandy Springs recently successfully rolled out its own police and fire departments. Counting police and fire employees, the city of 90,000 has only 196 total employees. Nearby Roswell, a city of 85,000 has over 1,400 employees. Furthermore, Sandy Springs’ budget is over $30 million less, and by most accounts provides a higher level of service.

The “Sandy Springs model” seems to be gaining steam. The city’s incorporation was perceived as such a success that four new cities—Johns Creek, Milton, Chattahoochee Hills and Dunwoody—have been formed in Georgia since 2006 employing operating models very similar to Sandy Springs (though severe revenue shortfalls in 2009 prompted the two smallest to scale back their contracts). And in 2008, city officials in the recently incorporated Central, Louisiana (population 27,000) hired a contractor to deliver a full range of municipal services—including public works, planning and zoning, code enforcement and administrative functions—as part of a three-year, $10.5 million contract.

Sandy Springs and other contract cities demonstrate something very powerful from a public administration standpoint: there’s hardly anything that local governments do that can’t be privatized, so there’s no reason policymakers shouldn’t think big on privatization.

Myths vs. Facts on Privatization

Privatization is a complex subject, and one that is commonly misunderstood. Three of the most prevalent myths include:

Myth: Privatization is partisan.

Fact: Privatization is not the domain of any one political party or ideology. In the U.S., privatization is used by leaders of both major political parties, and they have demonstrated that not only can politicians at all levels successfully privatize public services, but they can get re-elected after doing so. For example, former Indianapolis Mayor Stephen Goldsmith, a Republican, identified $400 million in savings and opened up over five dozen city services—including trash collection, pothole repair and wastewater services—to competitive bidding. Chicago Mayor Richard Daley, a Democrat, has privatized more than 40 services and, since 2005, has generated over $3 billion in privatization deals for the Chicago Skyway toll road, four downtown parking garages, and the city’s downtown parking meter system. And when Democrat Ed Rendell, governor of Pennsylvania, was mayor of Philadelphia, he saved $275 million by privatizing 49 city services, including golf courses, print shops, parking garages and correctional facilities.

Myth: Privatization involves a loss of public control.

Fact: This myth involves a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of privatization—that government loses control of an asset or service once it is privatized since the public sector is no longer providing that service. In well-structured privatization initiatives the government and taxpayers gain accountability. In fact, the legal foundation of a privatization initiative is a contract that spells out all of the responsibilities and performance expectations that the government partner will require of the contractor. No detail is too small for the contract. Any failure to meet the performance standards specified in the contract could expose the contractor to financial penalties, and in the worst-case scenario, termination of the contract.

So government never loses control—in fact, it can actually gain more control of outcomes—in well-crafted privatization arrangements. For example, state officials in Indiana have testified that they were able to require higher standards of performance from the concessionaire operating the Indiana Toll Road than the state itself could provide when it ran the road, precisely because they specified the standards they wanted in the contract and can now hold the concessionaire financially accountable for meeting them.

Myth: Privatization hurts public employees.

Fact: Privatization tends to encounter opposition from public employee unions who view it as a threat to their jobs and influence. Well-managed privatization initiatives need not put undue burden on public employees, however. Comprehensive examinations of privatization initiatives have found that they tend to result in few, if any, layoffs—those not retained by the new contractor usually either retire early or shift to other public sector positions—and that public employees can actually benefit in the long term when hired on by contractors, as private companies often present greater opportunities for upward career advancement, training and continuing education, and pay commensurate with performance, for example. Nevertheless, it is important that management communicate early and often with the public employee unions regarding privatization initiatives. In the event that city employee jobs are at risk, the city should develop a plan to manage public employee transitions.

Best Practices and Lessons Learned in Local Government Privatization

As is the case in all types of contracting, privatization can be implemented well or can be implemented poorly. A successful privatization process will ensure transparency, accountability and the delivery of high-performance services through a strong, performance-based contract. By using best practices and lessons learned from the experiences of other governments, the likelihood of achieving those results is greatly enhanced. Among them:

Rethink the status quo, and ask the “make or buy” question: Taking a page from management guru Peter Drucker, every “traditional” service or function should have to prove its worthiness and proper role and place within government. Contract cities like Sandy Springs were able to start with a blank slate and ask fundamental questions about what role government should play, such as “if we weren’t doing this yesterday, would we do it today?” Once they whittled the list down to those core functions deemed necessary, they then asked whether they should “make or buy” those services, opting to contract out as many services as possible to the private sector to get the best value for taxpayers. Traditional cities should not hesitate to ask these same questions regarding existing services.

Think big: Sandy Springs and the other contract cities prove that the central question on the subject of outsourcing should not be “what can we privatize?” but, rather, “what can’t we privatize?” Outside of public safety services, the courts and policymaking functions, the private sector has proven repeatedly in the contract cities that there is nothing in the routine operations of government—those things that citizens interface with most directly—that cannot be privatized.

Bundle services for better value: Local governments may find greater economies of scale, cost savings and/or value for money through bundling several—or even all—services in a given department (e.g., public works) or departmental subdivision (e.g., facility management and maintenance) into an outsourcing initiative, rather than treat individual services or functions separately. There have been several instances of governments moving toward this approach since 2008. Centennial, Colorado privatized all of its public works functions in 2008. Bonita Springs, Florida privatized all of its community development services (planning, zoning, permitting, inspections and code enforcement) that same year, and Pembroke Pines, Florida privatized its entire building and planning department in June 2009. Also, the state of Georgia signed a large-scale outsourcing contract for the management and maintenance of numerous secure-site facilities held by the Department of Corrections, Department of Juvenile Justice and Georgia Bureau of Investigation.

Focus on building procurement and contract management expertise: Successful privatization initiatives require good contract negotiation, management and monitoring skills on the part of city managers. The more that local governments use privatization, the greater the degree to which the city manager’s role will center on contract administration—monitoring and enforcing contracts to ensure that the contractor’s performance lives up to his contractual obligations. Staff must be properly trained in contracting best practices and, in particular, how to build specific service standards into agreements and monitor provider performance, in order to avoid possible ambiguities, misunderstandings and disputes.

Establish a centralized procurement unit: Governments should maintain an expert team of procurement and competition officials to guide individual departments in developing their privatization initiatives. This central unit will help to break down the “silos” that departments sometimes operate within and identify city-wide or enterprise-wide competition opportunities that might not otherwise be considered.

Apply the “Yellow Pages Test” through regular commercial activity inventories: Local government managers should regularly scour all government agencies, services and activities and classify each as either “inherently governmental” (i.e., services that should only be performed by public employees) or “commercial” (i.e., services offered by private sector vendors) in nature. This famous “Yellow Pages Test” helps government concentrate on delivering core, “inherently governmental” services while partnering with the private sector for commercial activities. In other words, undertaking a commercial activities inventory helps identify those areas in which government is engaged in the business of business, effectively competing against private sector business and undermining free enterprise and economic development.

The results of commercial activity inventories can be illuminating, especially with regard to the extent to which some governments compete against private enterprise to provide services. For example, Virginia’s first commercial activity inventory in 1999 identified 205 commercial activities being performed by over 38,000 state employees, accounting for nearly half of all state workers.

Utilize performance-based contracting: It is crucial that local governments identify good performance measures to fairly compare competing bids and accurately evaluate provider performance after the contract is awarded. Performance-based contracts should be used as much as possible to place the emphasis on obtaining the results the city wants achieved, rather than focusing merely on inputs and trying to dictate precisely how the service should be performed. Performance standards should be included in contracts and tied to compensation through financial incentives.

Establish guidelines for cost comparisons: Local governments should establish formal guidelines for cost comparisons to make sure that all costs are included in the “unit cost” of providing a service, so that an “apples-to-apples” comparison of competing bidders may be made. This is especially important in situations in which public employees may bid against private sector firms to provide a given service, as the public and private sectors operate under different rules.

Utilize “best value” contracting: Initiatives that are considered best practices for government procurement and service contracting utilize “best value” techniques where, rather than purchasing based on cost or “lowest bid” alone, governments choose the best mix of quality, cost and other factors in selecting a service vendor. Many privatization failures are linked to a low-cost selection where the allure of increased cost savings negatively impacted service quality.

Ensure contractor accountability through rigorous monitoring and performance evaluation: Regular monitoring and performance evaluations are essential to ensure accountability, transparency, and that the local government’s management and the service provider are on the same page. This can help address any problems that might arise early, before they become major setbacks.

Conclusion

Just moments after taking her oath of office in 2005 after the city’s incorporation, Sandy Springs Mayor Eva Galambos said, “We have harnessed the energy of the private sector to organize the major functions of city government instead of assembling our own bureaucracy. This we have done because we are convinced that the competitive model is what has made America so successful. And we are here to demonstrate that this same competitive model will lead to an efficient and effective local government.”

Local policymakers should periodically ask fundamental questions about how their governments operate and whether there is a better way. The experiences of Sandy Springs and the thousands of other local governments around the country—and indeed, around the world—that have embraced privatization demonstrate that there is another way to govern. When implemented with care, due diligence and a focus on maximizing competition, privatization is an approach that puts results, performance and outcomes first to deliver high-quality public services at a lower cost.

About the Author

Leonard Gilroy is the Director of Government Reform at Reason Foundation, a nonprofit think tank advancing free minds and free markets. Gilroy has a diversified background in policy research and implementation, with particular emphases on public-private partnerships, competition, government efficiency, transparency, accountability and government performance. Gilroy has worked closely with legislators and elected officials in Texas, Arizona, Louisiana, Utah, Virginia, California and several other states in efforts to design and implement market-based policy approaches, improve government performance, enhance accountability in government programs and reduce government spending.

Gilroy is the editor of the well-respected privatization newsletter Privatization Watch, and of the widely read Annual Privatization Report, which examines trends and chronicles the experiences of local, state and federal governments in bringing competition to public services. His articles have been featured in such leading publications as The Wall Street Journal, Los Angeles Times, New York Post, The Weekly Standard, Washington Times, Houston Chronicle, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Arizona Republic, San Diego Union-Tribune, Philadelphia Inquirer and The Salt Lake Tribune. Gilroy earned a B.A. and M.A. in Urban and Regional Planning from Virginia Tech.

Related Reason Studies

- Savings for San Diego: Outsourcing to Reduce Costs and Improve Services, by Leonard Gilroy and Adam Summers, December 2009

- Vehicle Fleet Maintenance/Management Outsourcing Opportunities: How San Diego and other cities can reduce the costs of vehicle fleet maintenance and management services, by Leonard Gilroy, Anthony Randazzo and Adam Summers, December 2009

- Building Maintenance and Management Outsourcing Opportunities: How San Diego and other cities can reduce the costs of facility management, by Leonard Gilroy and Adam Summers, December 2009

- Trends In Public and Contracted Government Services From 2002 to 2007: Privatization and outsourcing by local governments, by Mildred Warner and Amir Hefetz, August 2009

Endnotes

1 For more details on current trends in municipal privatization, see Reason Foundation’s Annual Privatization Report 2009. Earlier editions of the Annual Privatization Report are available at: https://reason.org/privatization-report/annual-privatization-report-20-28/

2 This evolution in governance is detailed in Stephen Goldsmith and William D. Eggers, Governing by Network: The New Shape of the Public Sector, (Brookings Institution Press: Washington D.C., 2004).

3 Over 100 studies of cost savings from privatization are reviewed in John Hilke, Cost Savings from Privatization: A Compilation of Study Findings, Reason Foundation How-to Guide No.6, (Los Angeles: Reason Foundation, 1993).

4 Mildred E. Warner and Amir Hefetz, Trends in Public and Contracted Government Services: 2002-2007, Reason Foundation, August 2009.

5 E.S. Savas, Privatization and Public-Private Partnerships (Chatham House Publishers: New York, NY, 2000) p. 72-73.