Our colleague Veronique de Rugy writing over at Reason.com had some good things to say about the housing recovery, particularly addressing some prevalent myths. As we discussed last week, there is a need for housing prices to decline. It isn’t clear exactly how much, but, as Vero also argues, it is not necessary for housing prices to reach pre-recession levels in order for the economy to recover.

It is certainly understandable for policymakers to want to avoid further price declines. And this often leads to a hesitant attitude towards any policy that might cause prices to drop—and also has driven the administration to lead the charge on a number of programs to prop up housing prices and temporarily juice housing demand.

Vero counters traditional thinking by arguing, pre-recession housing prices were a historic anomaly based on easy credit caused in part by misguided government policy:

“For most of American history housing prices grew at a relatively slow rate. It was only in the last 15 years that prices exploded. The factors behind this sudden change are a mixed bag of government policies that encouraged homeownership and cheap interest rates and a willingness by banks to lend to people who could only realistically afford to pay if housing prices doubled every two years. George Mason University economist Russ Roberts has a very good blog postexplaining why housing prices went up so fast.”

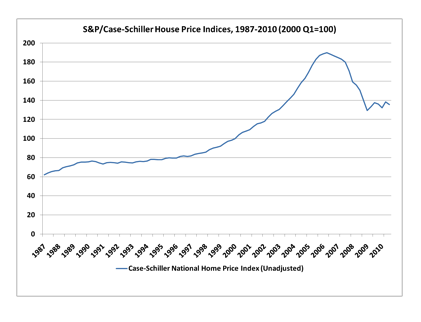

Consider the tables we provided last week showing the trend line in the Case-Schiller index as lower than where the index stands now, and also this chart Vero offers in her post:

The next issue Vero brings up to consider is that low prices are not necessarily bad. This certainly pushes back against traditional norms in thinking, and again that is understandable since low prices certainly are bad for those trying to sell their homes, and particularly those who made bad investment decisions in purchasing at the top of the market in 2006. Low prices also means banks are going to have to pay for some of their bad investment (i.e. mortgage loan) decisions as well if they have to foreclose.

However, consider this:”Low prices are very good for people who want to buy houses. They are also very good for low-income buyers who were priced out of the market in recent years.” Basically, we need to change the whole way we think about supporting housing: why favor the sellers over the buyers? Why favor the previous generation of homeowners over the next generation of homeowners. For every home sold at a low price there is a household benefiting. Why should policymakers favor one segment of the population over the other?

Now, if prices are falling and lawmakers don’t try to stop the decline this is not policy favoring the buyers. This is a neutral policy. If Washington does nothing to try and stop price declines and does nothing to try and intentionally cause a decline for the sake of buyers (i.e. a policy that would push prices lower to boost demand such as was attempted with the First-time Homebuyers Credit) then the market can self-correct, falling to its natural bottom—and from there it can grow unsubsidized and in balance with supply and demand signals for long-term stable, sustainable growth.

It is also worth noting that low prices mean increased demand—which would be good for getting the homebuilding market back up and running.

Here is the real kicker though, “most importantly, only lower prices can address one of the major problems of the real estate market: a bloated inventory of unsold homes.” We’ve discussed the shadow inventory a lot on this blog. Vero also notes that

“The inventory of existing homes stood at 3.71 million in November 2010, about where it was four years ago, according to the National Association of Realtors. Add to that the 197,000 new homes for sale and you can see just how bloated the inventory of unsold homes has become.

As Bloomberg’s Caroline Baum wrote in January: ‘The demand curve is downward sloping. What that means is demand for any good or service isn’t fixed. It depends on the price. A $1,000 cashmere sweater will find a lot more takers when it’s marked down to $500 in a post-Christmas sale. In general, the lower the price, the greater the quantity demanded. Hence, a reduction in prices could address this glut.'”

If we want a recovery in the housing market, we need a reduction in prices. We need to get back on the historical trend line for housing prices. This may not mean a sharp reduction in prices, but policymakers need to carefully reconsider the lens that they view housing policy through: the goal should not be housing recovery through price supports, the goal should be housing recovery through a removal of distortions on price and a willingness to let prices drop a little bit further so we can have long-term price growth and stability.

See more of our thoughts on housing prices here.

See Vero’s whole piece here.