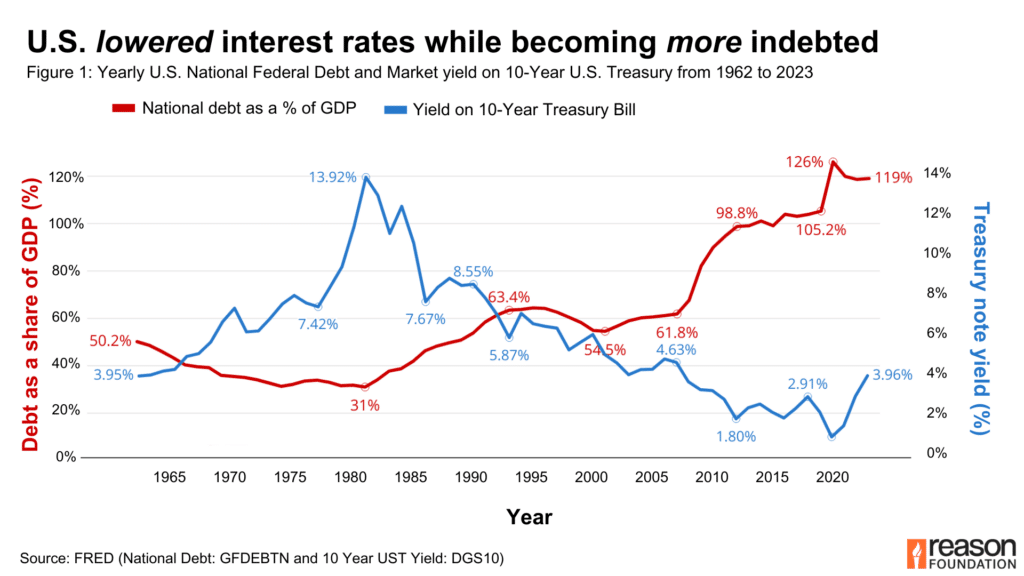

For the past two decades, the federal government has been racking up deficits with no expectation of ever running a surplus. This has been possible because of a belief that, for the U.S., the classic accounting link between increasing debt and borrowing costs does not apply.

Most countries can’t spend much more than they make. High debt sometimes forces a country to offer higher bond yields to compensate investors to continue purchasing increasingly riskier bonds. The threat of debt overhang—when an entity has so much debt that it can’t borrow more money to cover the costs of servicing its existing debt—keeps countries, like companies, from being able to take on too much debt.

The U.S., however, seemed immune to this relationship between increased debt and risk because the world views U.S. Treasury bills as the safest asset conceivable, as risk-free as it gets. The theory goes that America’s unrivaled military, economic, and political power gives it incredible revenue-generating capacity and makes it the safest borrower, no matter how much debt it has.

This theory has allowed the U.S. to achieve the near-impossible: to become more indebted while lowering the compensation given to a large number of new lenders.

As a result, some naive economists have come to the conclusion that the U.S. has gained “self-financing” status, allowing it to borrow without consequence. A mere decade or two of low interest rates have led many to conclude that “deficits don’t matter” and that there is no reason to reduce federal spending.

To be sure, this view never gained a consensus among academic economists, but the era of low interest rates did lend it a surface plausibility. With the magnitude of needed Treasury issuances projected for the next decade, we may have now reached a turning point that reveals just how naive this line of reasoning was—and how grave the consequences may be.

The debt becomes unaffordable

The federal debt is becoming harder to afford. According to the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) most recent estimate, federal interest expenses are expected to grow to $1.7 trillion by 2034, equivalent to 4.1% of gross domestic product (GDP), one of the largest single budgetary expenses. A report by Manhattan Institute fellow Jessica Riedl found that, assuming current-policy tax cuts and spending extensions, even with the CBO’s optimistic interest-rate assumptions, net interest will become the largest government expense by 2042, surpassing Medicare and Social Security.

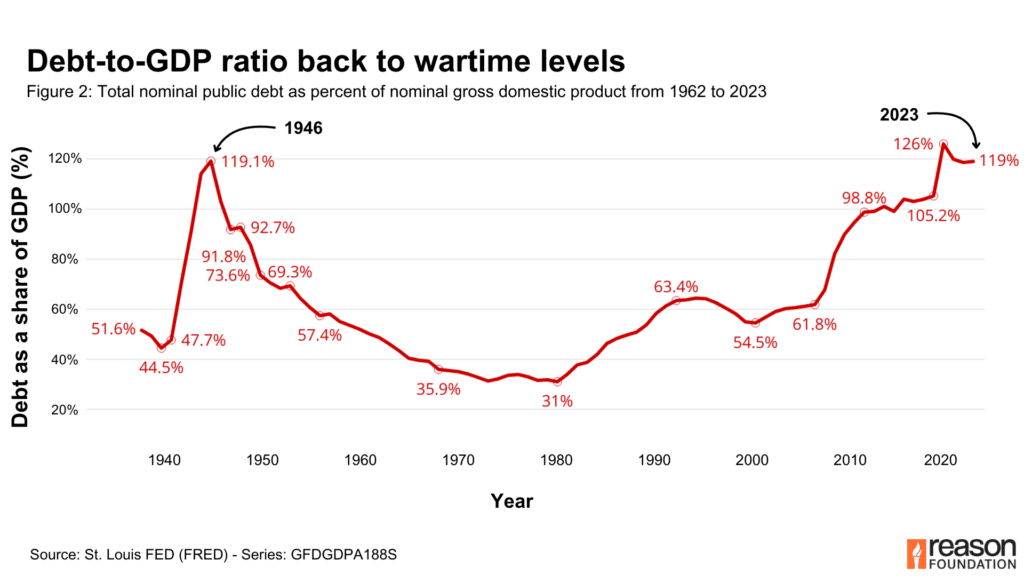

The U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio reached 119% in 1946 after World War I and II but was effectively lowered back to around mid-30% in the ‘70s. In the ‘80s, it started to rise once again. By 2024, it reached 119% of GDP—but this time, entitlement obligations made it more complicated for it to ever fall again.

Debt growth is not a revenue problem; it’s a spending problem—specifically, a mandatory entitlement spending problem. Medicare and Social Security, the two largest government expenses, are expected to demand about 17% of GDP annually by 2034. The present value of Medicare and Social Security unfunded liabilities in 2023 was $73.2 trillion. If these unfunded commitments were included in the national debt calculations, it would amount to $106 trillion, making the debt-to-GDP ratio 382%. This level of committed spending, which far outstrips the U.S.’s revenue-generating capacity, is forecasted to require trillions more dollars in debt issuance.

The U.S.’s debt trajectory has reached a scale that raises legitimate questions about the federal government’s ability to repay its bonds on time. This is why, in August 2023, Fitch downgraded the country’s long-term credit rating from AAA to AA+.

But, aren’t we all leveraged?

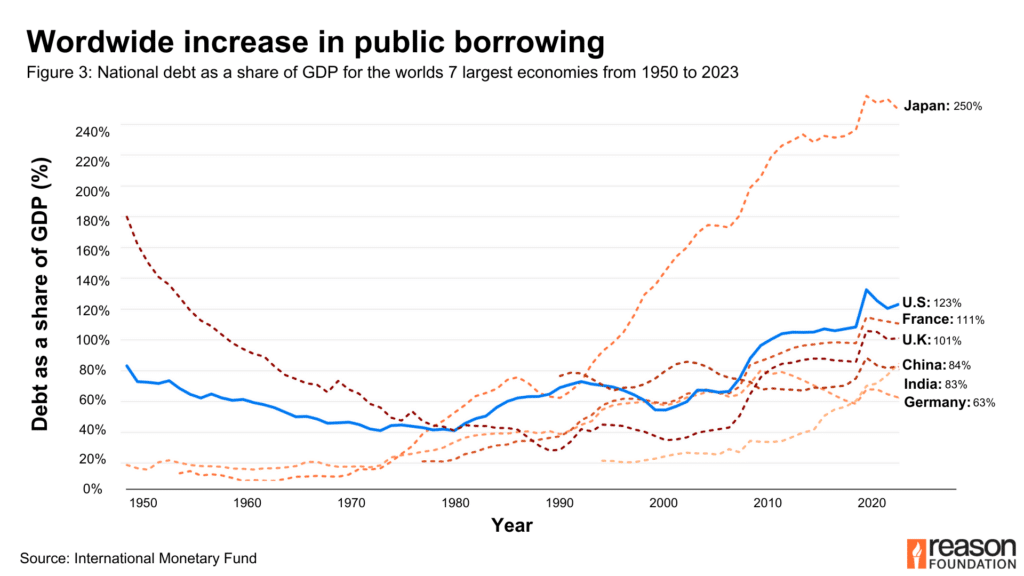

Many raise the most common concern regarding the federal debt: that, in the medium to longer term, debt threatens the U.S.’s creditworthiness and, therefore, its monetary policy and general interest rates. This view makes several assumptions: not only that the U.S.’s creditworthiness decays, but also that it decays faster than other countries. A country’s counterparty (default) risk is not objective; it is contextual. Risk, like return, is marginal.

Though the enlarged federal U.S. debt and its growing interest costs have put into question the country’s ability to repay its creditors, all countries have become and continue to become more indebted.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF):

Global public debt is very high. It is expected to exceed $100 trillion, or about 93 percent of global gross domestic product by the end of this year [2024] and will approach 100 percent of GDP by 2030. This is 10 percentage points of GDP above 2019, that is, before the pandemic.

For an average economy to ensure a high likelihood of debt stabilization, a cumulative tightening of about 3.8 percent of GDP over six years would be needed. In countries where debt is not projected to stabilize, such as China and the United States, the required effort is substantially greater.

The largest spending budget items do not seem to be going anywhere. As in the U.S., countries worldwide are only projected to spend more on old-age and healthcare promises. Further, commitments to a green transition or protectionism add to the bill. Growing geopolitical tensions have created a defense and energy-security arms race. Almost all the top government spending items seem untouchable.

With the world’s governments becoming more leveraged, the impact of federal debt on interest rates might take some time. The U.S.’s creditworthiness may be decaying, but so is everyone else’s.

However, debt poses a more immediate concern for fiscal and monetary policy, one that goes beyond doubts about creditworthiness. There might simply be no market for the scale of treasury issuances needed to close the books.

A more immediate limit: the market

The most recent CBO estimate claims that U.S. federal debt held by the public will increase from $26.2 trillion at the end of 2023 to $50.7 trillion by the end of 2034. In other words, the federal government will have to find buyers for $24.5 trillion of debt in the next 10 years.

It is unclear if the U.S. can sell so much debt without significantly increasing the compensation for lending, that is, the interest rates offered on its bonds—which has consequences for all interest rates.

As the chair of the Treasury Market Practices Group, Casey Spezzano summarized concerns about the capacity of debt dealers to absorb increased issuance:

[Debt] Issuance has gone up almost threefold in the last 10 years and the anticipation is for it to close to double to $50 trillion outstanding in the next 10 years, whereas dealer balance sheets haven’t grown at that magnitude.

You’re trying to put more Treasuries through the same pipes, but those pipes aren’t getting any bigger.

Who buys most of the U.S. government’s debt? Americans. Only 29% of outstanding U.S. public debt is foreign-owned, with the rest held domestically: 27% by the Federal Reserve, 19% by mutual funds, 9% by depository institutions (banks), 9% by state and local governments, 5% by pensions, and 5% by insurance companies.

The Federal Reserve is the single largest buyer of federal debt. Though independent, the Fed buys treasury securities on the secondary market via open market operations (OMO), creating new money to finance government borrowing and expanding the monetary base.

The Federal Reserve cannot purchase U.S. government debt for free—instead, the cost of doing so is distributed. When the Federal Reserve creates money to buy treasuries, the dollar’s purchasing power is diluted, creating inflation. This mechanism is simply a creative way to impose the costs of debt purchases on American households and businesses, eroding their savings and reducing real incomes.

Though the Federal Reserve is the top individual buyer of federal debt, it is unlikely the government will be able to pass on the costs of the scale of Treasuries that need to be issued in the next two to three decades without significant inflation—which in itself puts upward pressure on interest rates as investors take it into account when pricing assets.

Further, incoming increases in capital requirements for U.S. banks, following the trajectory set by European banks and international regulatory accords, will constrain their balance sheet capacity for U.S. Treasury securities.

As U.S. debt and related interest costs take up a progressively larger share of the U.S. economy, making markets for U.S. Treasury bills might require persuading marginal buyers—i.e., the most interest-rate-sensitive investors. This would pressure the government to offer higher yields, driving up overall borrowing costs.

The world’s economy might not have the capacity—or interest—to absorb the scale of Treasury issuance required to sustain current spending levels at low yields. To attract creditors, the federal government may need to offer significantly higher returns, which means higher interest rates.

The Federal Reserve’s triple mandate: unemployment, inflation, and…debt management?

The U.S. government might be unable to sell the magnitude of debt it will have to offer to markets at low yields. Markets are growing skeptical of U.S. creditworthiness and, most importantly, may no longer have an appetite for the scale of Treasuries the U.S. government needs to sell at uncompetitive yields. If the federal government wants to offer the world another $25 trillion in debt in the next decade, it might need to offer better returns. Given that debt service is one of the largest federal expenses, a small increase in Treasury yields above expectations can have grave consequences.

If this is true, it also marks a new era of monetary and fiscal policy, where the Fed is facing a new constraint: its own debt. Just like in third-world countries, for the first time in the United States, unemployment and inflation face a new rival in the decision to set interest rates: making sure people keep buying the debt.